AURIOL

OR

THE ELIXIR OF LIFE

BY W. HARRISON AINSWORTH

AUTHOR OF "THE TOWER OF LONDON"

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY H. K. BROWNE

AUTHOR'S COPYRIGHT EDITION

LONDON

GEORGE ROUTLEDGE AND SONS, Limited

Broadway, Ludgate Hill

1898

Printed by Ballantyne, Hanson & Co.

At the Ballantyne Press

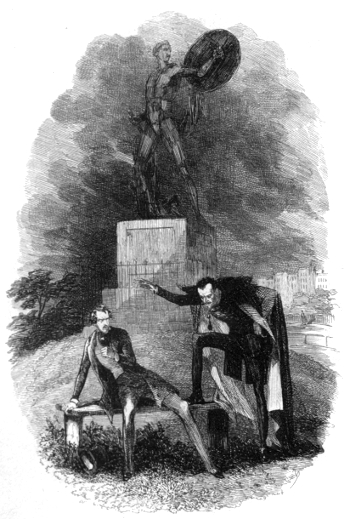

The mysterious interview in Hyde Park

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE—1599—DR. LAMB

BOOK THE FIRST—EBBA—

CHAPTER I. THE RUINED HOUSE IN THE VAUXHALL ROAD

CHAPTER II. THE DOG-FANCIER

CHAPTER III. THE HAND AND THE CLOAK

CHAPTER IV. THE IRON-MERCHANT'S DAUGHTER

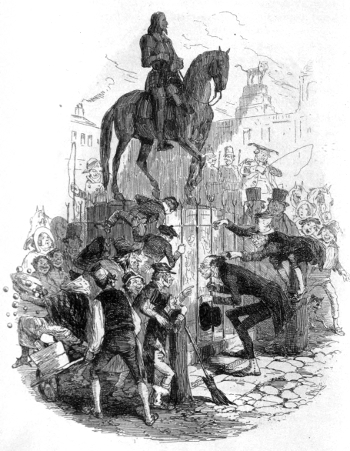

CHAPTER V. THE MEETING NEAR THE STATUE

CHAPTER VI. THE CHARLES THE SECOND SPANIEL

CHAPTER VII. THE HAND AGAIN!

CHAPTER VIII. THE BARBER OF LONDON

CHAPTER IX. THE MOON IN THE FIRST QUARTER

CHAPTER X. THE STATUE AT CHARING CROSS

CHAPTER XI. PREPARATIONS

CHAPTER XII. THE CHAMBER OF MYSTERY

INTERMEAN—1800—

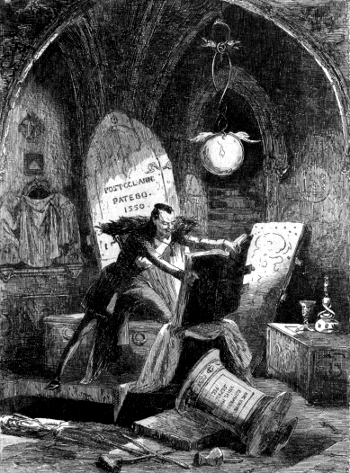

CHAPTER I. THE TOMB OF THE ROSICRUCIAN

CHAPTER II. THE COMPACT

CHAPTER III. IRRESOLUTION

CHAPTER IV. EDITH TALBOT

CHAPTER V. THE SEVENTH NIGHT

BOOK THE SECOND—CYPRIAN ROUGEMONT—

CHAPTER I. THE CELL

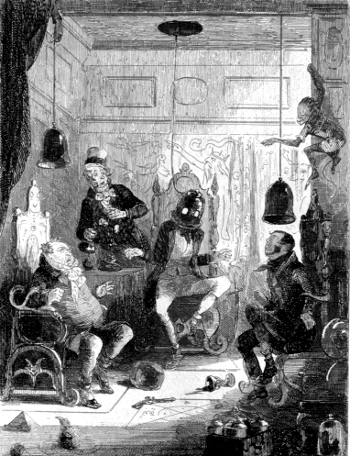

CHAPTER II. THE ENCHANTED CHAIRS

CHAPTER III. GERARD PASTON

CHAPTER IV. THE PIT

CHAPTER V. NEW PERPLEXITIES

CHAPTER VI. DR. LAMB AGAIN

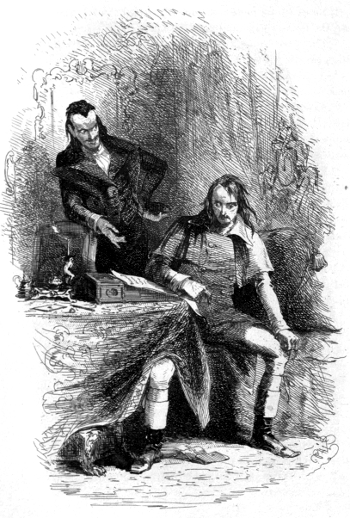

THE OLD LONDON MERCHANT

A NIGHT'S ADVENTURE IN ROME—

CHAPTER I. SANTA MARIA MAGGIORE

CHAPTER II. THE MARCHESA

BOOK THE FIRST—EBBA—

CHAPTER I. THE RUINED HOUSE IN THE VAUXHALL ROAD

CHAPTER II. THE DOG-FANCIER

CHAPTER III. THE HAND AND THE CLOAK

CHAPTER IV. THE IRON-MERCHANT'S DAUGHTER

CHAPTER V. THE MEETING NEAR THE STATUE

CHAPTER VI. THE CHARLES THE SECOND SPANIEL

CHAPTER VII. THE HAND AGAIN!

CHAPTER VIII. THE BARBER OF LONDON

CHAPTER IX. THE MOON IN THE FIRST QUARTER

CHAPTER X. THE STATUE AT CHARING CROSS

CHAPTER XI. PREPARATIONS

CHAPTER XII. THE CHAMBER OF MYSTERY

INTERMEAN—1800—

CHAPTER I. THE TOMB OF THE ROSICRUCIAN

CHAPTER II. THE COMPACT

CHAPTER III. IRRESOLUTION

CHAPTER IV. EDITH TALBOT

CHAPTER V. THE SEVENTH NIGHT

BOOK THE SECOND—CYPRIAN ROUGEMONT—

CHAPTER I. THE CELL

CHAPTER II. THE ENCHANTED CHAIRS

CHAPTER III. GERARD PASTON

CHAPTER IV. THE PIT

CHAPTER V. NEW PERPLEXITIES

CHAPTER VI. DR. LAMB AGAIN

THE OLD LONDON MERCHANT

A NIGHT'S ADVENTURE IN ROME—

CHAPTER I. SANTA MARIA MAGGIORE

CHAPTER II. THE MARCHESA

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

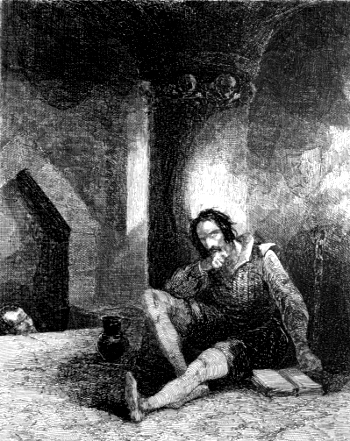

PROLOGUE

1599

DR. LAMB

The Sixteenth Century drew to a close. It was the last day of the last year, and two hours only were wanting to the birth of another year and of another century.

The night was solemn and beautiful. Myriads of stars paved the deep vault of heaven; the crescent moon hung like a silver lamp in the midst of them; a stream of rosy and quivering light, issuing from the north, traversed the sky, like the tail of some stupendous comet; while from its point of effluence broke forth, ever and anon, coruscations rivalling in splendour and variety of hue the most brilliant discharge of fireworks.

A sharp frost prevailed; but the atmosphere was clear and dry, and neither wind nor snow aggravated the wholesome rigour of the season. The water lay in thick congealed masses around the conduits and wells, and the buckets were frozen on their stands. The thoroughfares were sheeted with ice, and dangerous to horsemen and vehicles; but the footways were firm and pleasant to the tread.

Here and there, a fire was lighted in the streets, round which ragged urchins and mendicants were collected, roasting fragments of meat stuck upon iron prongs, or quaffing deep draughts of metheglin and ale out of leathern cups. Crowds were collected in the open places, watching the wonders in the heavens, and drawing auguries from them, chiefly sinister, for most of the beholders thought the signs portended the speedy death of the queen, and the advent of a new monarch from the north—a safe and easy interpretation, considering the advanced age and declining health of the illustrious Elizabeth, together with the known appointment of her successor, James of Scotland.

Notwithstanding the early habits of the times, few persons had retired to rest, an universal wish prevailing among the citizens to see the new year in, and welcome the century accompanying it. Lights glimmered in most windows, revealing the holly-sprigs and laurel-leaves stuck thickly in their diamond panes; while, whenever a door was opened, a ruddy gleam burst across the street, and a glance inside the dwelling showed its inmates either gathered round the glowing hearth, occupied in mirthful sports—fox-i'-th'-hole, blind-man's buff, or shoe-the-mare—or seated at the ample board groaning with Christmas cheer.

Music and singing were heard at every corner, and bands of comely damsels, escorted by their sweethearts, went from house to house, bearing huge brown bowls dressed with ribands and rosemary, and filled with a drink called "lamb's-wool," composed of sturdy ale, sweetened with sugar, spiced with nutmeg, and having toasts and burnt crabs floating within it—a draught from which seldom brought its pretty bearers less than a groat, and occasionally a more valuable coin.

Such was the vigil of the year sixteen hundred.

On this night, and at the tenth hour, a man of striking and venerable appearance was seen to emerge upon a small wooden balcony, projecting from a bay-window near the top of a picturesque structure situated at the southern extremity of London Bridge.

The old man's beard and hair were as white as snow—the former descending almost to his girdle; so were the thick, overhanging brows that shaded his still piercing eyes. His forehead was high, bald, and ploughed by innumerable wrinkles. His countenance, despite its death-like paleness, had a noble and majestic cast; and his figure, though worn to the bone by a life of the severest study, and bent by the weight of years, must have been once lofty and commanding. His dress consisted of a doublet and hose of sad-coloured cloth, over which he wore a loose gown of black silk. His head was covered by a square black cap, from beneath which his silver locks strayed over his shoulders.

Known by the name of Doctor Lamb, and addicted to alchemical and philosophical pursuits, this venerable personage was esteemed by the vulgar as little better than a wizard. Strange tales were reported and believed of him. Amongst others, it was said that he possessed a familiar, because he chanced to employ a deformed, crack-brained dwarf, who assisted him in his operations, and whom he appropriately enough denominated Flapdragon.

Doctor Lamb's gaze was fixed intently upon the heavens, and he seamed to be noting the position of the moon with reference to some particular star.

After remaining in this posture for a few minutes, he was about to retire, when a loud crash arrested him, and he turned to see whence it proceeded.

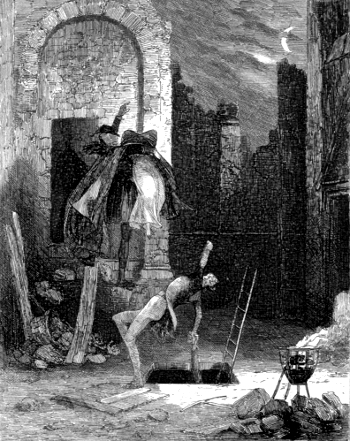

Immediately before him stood the Southwark Gateway—a square stone building, with a round, embattled turret at each corner, and a flat leaden roof, planted with a forest of poles, fifteen or sixteen feet high, garnished with human heads. To his surprise, the doctor perceived that two of these poles had just been overthrown by a tall man, who was in the act of stripping them of their grisly burdens.

Having accomplished his object, the mysterious plunderer thrust his spoil into a leathern bag with which he was provided, tied its mouth, and was about to take his departure by means of a rope-ladder attached to the battlements, when his retreat was suddenly cut off by the gatekeeper, armed with a halberd, and bearing a lantern, who issued from a door opening upon the leads.

The baffled marauder looked round, and remarking the open window at which Doctor Lamb was stationed, hurled the sack and its contents through it. He then tried to gain the ladder, but was intercepted by the gatekeeper, who dealt him a severe blow on the head with his halberd. The plunderer uttered a loud cry, and attempted to draw his sword; but before he could do so, he received a thrust in the side from his opponent. He then fell, and the gatekeeper would have repeated the blow, if the doctor had not called to him to desist.

"Do not kill him, good Baldred," he cried. "The attempt may not be so criminal as it appears. Doubtless, the mutilated remains which the poor wretch has attempted to carry off are those of his kindred, and horror at their exposure must have led him to commit the offence."

"It may be, doctor," replied Baldred; "and if so I shall be sorry I have hurt him. But I am responsible for the safe custody of these traitorous relics, and it is as much as my own head is worth to permit their removal."

"I know it," replied Doctor Lamb; "and you are fully justified in what you have done. It may throw some light upon the matter, to know whose miserable remains have been disturbed."

"They were the heads of two rank papists," replied Baldred, "who were decapitated on Tower Hill, on Saint Nicholas's Day, three weeks ago, for conspiring against the queen."

"But their names?" demanded the doctor. "How were they called?"

"They were father and son," replied Baldred—"Sir Simon Darcy and Master Reginald Darcy. Perchance they were known to your worship?"

"Too well—too well!" replied Doctor Lamb, in a voice of emotion that startled his hearer. "They were near kinsmen of mine own. What is he like who has made this strange attempt?"

"Of a verity, a fair youth," replied Baldred, holding down the lantern. "Heaven grant I have not wounded him to the death! No, his heart still beats. Ha! here are his tablets," he added, taking a small book from his doublet; "these may give the information you seek. You were right in your conjecture, doctor. The name herein inscribed is the same as that borne by the others—Auriol Darcy."

"I see it all," cried Lamb. "It was a pious and praiseworthy deed. Bring the unfortunate youth to my dwelling, Baldred, and you shall be well rewarded. Use despatch, I pray you."

As the gatekeeper essayed to comply, the wounded man groaned deeply, as if in great pain.

"Fling me the weapon with which you smote him," cried Doctor Lamb, in accents of commiseration, "and I will anoint it with the powder of sympathy. His anguish will be speedily abated."

"I know your worship can accomplish wonders," cried Baldred, throwing the halberd into the balcony. "I will do my part as gently as I can."

And as the alchemist took up the weapon, and disappeared through the window, the gatekeeper lifted the wounded man by the shoulders, and conveyed him down a narrow, winding staircase to a lower chamber. Though he proceeded carefully, the sufferer was put to excruciating pain; and when Baldred placed him on a wooden bench, and held a lamp towards him, he perceived that his features were darkened and distorted.

"I fear it's all over with him," murmured the gatekeeper; "I shall have a dead body to take to Doctor Lamb. It would be a charity to knock him on the head, rather than let him suffer thus. The doctor passes for a cunning man, but if he can cure this poor youth without seeing him, by the help of his sympathetic ointment, I shall begin to believe, what some folks avouch, that he has relations with the devil."

While Baldred was ruminating in this manner, a sudden and extraordinary change took place in the sufferer. As if by magic, the contraction of the muscles subsided; the features assumed a wholesome hue, and the respiration was no longer laborious. Baldred stared as if a miracle had been wrought.

Now that the countenance of the youth had regained its original expression, the gatekeeper could not help being struck by its extreme beauty. The face was a perfect oval, with regular and delicate features. A short silken moustache covered the upper lip, which was short and proud, and a pointed beard terminated the chin. The hair was black, glossy, and cut short, so as to disclose a highly intellectual expanse of brow.

The youth's figure was slight, but admirably proportioned. His attire consisted of a black satin doublet, slashed with white, hose of black silk, and a short velvet mantle. His eyes were still closed, and it was difficult to say what effect they might give to the face when they lighted it up; but notwithstanding its beauty, it was impossible not to admit that a strange, sinister, and almost demoniacal expression pervaded the countenance.

All at once, and with as much suddenness as his cure had been effected, the young man started, uttering a piercing cry, and placed his hand to his side.

"Caitiff!" he cried, fixing his blazing eyes on the gatekeeper, "why do you torture me thus? Finish me at once—Oh!"

And overcome by anguish, he sank back again.

"I have not touched you, sir," replied Baldred. "I brought you here to succour you. You will be easier anon. Doctor Lamb must have wiped the halberd," he added to himself.

Another sudden change. The pain fled from the sufferer's countenance, and he became easy as before.

"What have you done to me?" he asked, with a look of gratitude; "the torture of my wound has suddenly ceased, and I feel as if a balm had been dropped into it. Let me remain in this state if you have any pity—or despatch me, for my late agony was almost insupportable."

"You are cared for by one who has greater skill than any chirurgeon in London," replied Baldred. "If I can manage to transport you to his lodgings, he will speedily heal your wounds."

"Do not delay, then," replied Auriol faintly; "for though I am free from pain, I feel that my life is ebbing fast away."

"Press this handkerchief to your side, and lean on me," said Baldred. "Doctor Lamb's dwelling is but a step from the gateway—in fact, the first house on the bridge. By the way, the doctor declares he is your kinsman."

"It is the first I ever heard of him," replied Auriol faintly; "but take me to him quickly, or it will be too late."

In another moment they were at the doctor's door. Baldred tapped against it, and the summons was instantly answered by a diminutive personage, clad in a jerkin of coarse grey serge, and having a leathern apron tied round his waist. This was Flapdragon.

Blear-eyed, smoke-begrimed, lantern-jawed, the poor dwarf seemed as if his whole life had been spent over the furnace. And so, in fact, it had been. He had become little better than a pair of human bellows. In his hand he held the halberd with which Auriol had been wounded.

"So you have been playing the leech, Flapdragon, eh?" cried Baldred.

"Ay, marry have I," replied the dwarf, with a wild grin, and displaying a wolfish set of teeth. "My master ordered me to smear the halberd with the sympathetic ointment. I obeyed him: rubbed the steel point, first on one side, then on the other; next wiped it; and then smeared it again."

"Whereby you put the patient to exquisite pain," replied Baldred; "but help me to transport him to the laboratory."

"I know not if the doctor will care to be disturbed," said Flapdragon. "He is busily engaged on a grand operation."

"I will take the risk on myself," said Baldred. "The youth will die if he remains here. See, he has fainted already!"

Thus urged, the dwarf laid down the halberd, and between the two, Auriol was speedily conveyed up a wide oaken staircase to the laboratory. Doctor Lamb was plying the bellows at the furnace, on which a large alembic was placed, and he was so engrossed by his task that he scarcely noticed the entrance of the others.

"Place the youth on the ground, and rear his head against the chair," he cried, hastily, to the dwarf. "Bathe his brows with the decoction in that crucible. I will attend to him anon. Come to me on the morrow, Baldred, and I will repay thee for thy trouble. I am busy now."

"These relics, doctor," cried the gatekeeper, glancing at the bag, which was lying on the ground, and from which a bald head protruded—"I ought to take them back with me."

"Heed them not—they will be safe in my keeping," cried Doctor Lamb impatiently; "to-morrow—to-morrow."

Casting a furtive glance round the laboratory, and shrugging his shoulders, Baldred departed; and Flapdragon having bathed the sufferer's temples with the decoction, in obedience to his master's injunctions, turned to inquire what he should do next.

"Begone!" cried the doctor, so fiercely that the dwarf darted out of the room, clapping the door after him.

Doctor Lamb then applied himself to his task with renewed ardour, and in a few seconds became wholly insensible of the presence of a stranger.

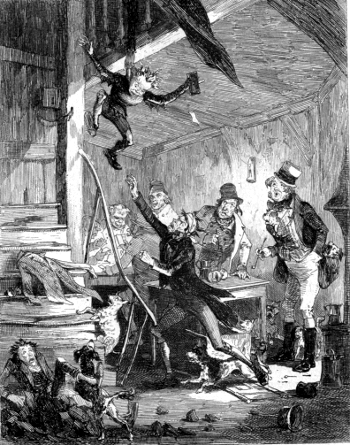

Revived by the stimulant, Auriol presently opened his eyes, and gazing round the room, thought he must be dreaming, so strange and fantastical did all appear. The floor was covered with the implements used by the adept—bolt-heads, crucibles, cucurbites, and retorts, scattered about without any attempt at arrangement. In one corner was a large terrestrial sphere: near it was an astrolabe, and near that a heap of disused glass vessels. On the other side lay a black, mysterious-looking book, fastened with brazen clasps. Around it were a ram's horn, a pair of forceps, a roll of parchment, a pestle and mortar, and a large plate of copper, graven with the mysterious symbols of the Isaical table. Near this was the leathern bag containing the two decapitated heads, one of which had burst forth. On a table at the farther end of the room, stood a large open volume, with parchment leaves, covered with cabalistical characters, referring to the names of spirits. Near it were two parchment scrolls, written in letters, respectively denominated by the Chaldaic sages, "the Malachim," and "the Passing of the River." One of these scrolls was kept in its place by a skull. An ancient and grotesque-looking brass lamp, with two snake-headed burners, lighted the room. From the ceiling depended a huge scaly sea-monster, with outspread fins, open jaws garnished with tremendous teeth, and great goggling eyes. Near it hung a celestial sphere. The chimney-piece, which was curiously carved, and projected far into the room, was laden with various implements of hermetic science. Above it were hung dried bats and flitter-mice, interspersed with the skulls of birds and apes. Attached to the chimney-piece was a horary, sculptured in stone, near which hung a large starfish. The fireplace was occupied by the furnace, on which, as has been stated, was placed an alembic, communicating by means of a long serpentine pipe with a receiver. Within the room were two skeletons, one of which, placed behind a curtain in the deep embrasure of the window, where its polished bones glistened in the white moonlight, had a horrible effect. The other enjoyed more comfortable quarters near the chimney, its fleshless feet dangling down in the smoke arising from the furnace.

Doctor Lamb, meanwhile, steadily pursued his task, though he ever and anon paused, to fling certain roots and drugs upon the charcoal. As he did this, various-coloured flames broke forth—now blue, now green, now blood-red.

Tinged by these fires, the different objects in the chamber seemed to take other forms, and to become instinct with animation. The gourd-shaped cucurbites were transformed into great bloated toads bursting with venom; the long-necked bolt-heads became monstrous serpents; the worm-like pipes turned into adders; the alembics looked like plumed helmets; the characters on the Isaical table, and those on the parchments, seemed traced in fire, and to be ever changing; the sea-monster bellowed and roared, and, flapping his fins, tried to burst from his hook; the skeletons wagged their jaws, and raised their fleshless fingers in mockery, while blue lights burnt in their eyeless sockets; the bellows became a prodigious bat fanning the fire with its wings; and the old alchemist assumed the appearance of the archfiend presiding over a witches' sabbath.

Auriol's brain reeled, and he pressed his hand to his eyes, to exclude these phantasms from his sight. But even thus they pursued him; and he imagined he could hear the infernal riot going on around him.

Suddenly, he was roused by a loud joyful cry, and, uncovering his eyes, he beheld Doctor Lamb pouring the contents of the matrass—a bright, transparent liquid—into a small phial. Having carefully secured the bottle with a glass stopper, the old man held it towards the light, and gazed at it with rapture.

"At length," he exclaimed aloud—"at length, the great work is achieved. With the birth of the century now expiring I first saw light, and the draught I hold in my hand shall enable me to see the opening of centuries and centuries to come. Composed of the lunar stones, the solar stones, and the mercurial stones—prepared according to the instructions of the Rabbi Ben Lucca—namely, by the separation of the pure from the impure, the volatilisation of the fixed, and the fixing of the volatile—this elixir shall renew my youth, like that of the eagle, and give me length of days greater than any patriarch ever enjoyed."

While thus speaking, he held up the sparkling liquid, and gazed at it like a Persian worshipping the sun.

"To live for ever!" he cried, after a pause—"to escape the jaws of death just when they are opening to devour me!—to be free from all accidents!—'tis a glorious thought! Ha! I bethink me, the rabbi said there was one peril against which the elixir could not guard me—one vulnerable point, by which, like the heel of Achilles, death might reach me! What is it!—where can it lie?"

And he relapsed into deep thought.

"This uncertainty will poison all my happiness," he continued; "I shall live in constant dread, as of an invisible enemy. But no matter! Perpetual life!—perpetual youth!—what more need be desired?"

"What more, indeed!" cried Auriol.

"Ha!" exclaimed the doctor, suddenly recollecting the wounded man, and concealing the phial beneath his gown.

"Your caution is vain, doctor," said Auriol. "I have heard what you have uttered. You fancy you have discovered the elixir vitæ."

"Fancy I have discovered it!" cried Doctor Lamb. "The matter is past all doubt. I am the possessor of the wondrous secret, which the greatest philosophers of all ages have sought to discover—the miraculous preservative of the body against decay."

"The man who brought me hither told me you were my kinsman," said Auriol. "Is it so?"

"It is," replied the doctor, "and you shall now learn the connection that subsists between us. Look at that ghastly relic," he added, pointing to the head protruding from the bag: "that was once my son Simon. His son's head is within the sack—your father's head—so that four generations are brought together."

"Gracious Heaven!" exclaimed the young man, raising himself on his elbow. "You, then, are my great-grandsire. My father supposed you had died in his infancy. An old tale runs in the family that you were charged with sorcery, and fled to avoid the stake."

"It is true that I fled, and took the name I bear at present," replied the old man, "but I need scarcely say that the charge brought against me was false. I have devoted myself to abstrusest science, have held commune with the stars, and have wrested the most hidden secrets from Nature—but that is all. Two crimes alone have stained my soul; but both, I trust, have been expiated by repentance."

"Were they deeds of blood?" asked Auriol.

"One was so," replied Darcy, with a shudder. "It was a cowardly and treacherous deed, aggravated by the basest ingratitude. Listen, and you shall hear how it chanced. A Roman rabbi, named Ben Lucca, skilled in hermetic science, came to this city. His fame reached me, and I sought him out, offering myself as his disciple. For months, I remained with him in his laboratory—working at the furnace, and poring over mystic lore. One night he showed me that volume, and, pointing to a page within it, said: 'Those characters contain the secret of confecting the elixir of life. I will now explain them to you, and afterwards we will proceed to the operation.' With this, he unfolded the mystery; but he bade me observe, that the menstruum was defective on one point. Wherefore, he said, 'there will still be peril from some hidden cause.' Oh, with what greediness I drank in his words! How I gazed at the mystic characters, as he explained their import! What visions floated before me of perpetual youth and enjoyment. At that moment a demon whispered in my ear, 'This secret must be thine own. No one else must possess it.'"

"Ha!" exclaimed Auriol, starting.

"The evil thought was no sooner conceived than acted upon," pursued Darcy. "Instantly drawing my poniard, I plunged it to the rabbi's heart. But mark what followed. His blood fell upon the book, and obliterated the characters; nor could I by any effort of memory recall the composition of the elixir."

"When did you regain the secret?" asked Auriol curiously.

"To-night," replied Darcy—"within this hour. For nigh fifty years after that fatal night I have been making fruitless experiments. A film of blood has obscured my mental sight. I have proceeded by calcitration, solution, putrefaction—have produced the oils which will fix crude mercury, and convert all bodies into sol and luna; but I have ever failed in fermenting the stone into the true elixir. To-night, it came into my head to wash the blood-stained page containing the secret with a subtle liquid. I did so; and doubting the efficacy of the experiment, left it to work, while I went forth to breathe the air at my window. My eyes were cast upwards, and I was struck with the malignant aspect of my star. How to reconcile this with the good fortune which has just befallen me, I know not—but so it was. At this juncture, your rash but pious attempt occurred. Having discovered our relationship, and enjoined the gatekeeper to bring you hither, I returned to my old laboratory. On glancing towards the mystic volume, what was my surprise to see the page free from blood!"

Auriol uttered a slight exclamation, and gazed at the book with superstitious awe.

"The sight was so surprising that I dropped the sack I had brought with me," pursued Darcy. "Fearful of again losing the secret, I nerved myself to the task, and placing fuel on the fire, dismissed my attendant with brief injunctions relative to you. I then set to work. How I have succeeded, you perceive. I hold in my hand the treasure I have so long sought—so eagerly coveted. The whole world's wealth should not purchase it from me."

Auriol gazed earnestly at his aged relative, but he said nothing.

"In a few moments I shall be as full of vigour and activity as yourself," continued Darcy. "We shall be no longer the great-grandsire and his descendant, but friends—companions—equals,—equals in age, strength, activity, beauty, fortune—for youth is fortune—ha! ha! Methinks I am already young again!"

"You spoke of two crimes with which your conscience was burdened," remarked Auriol. "You have mentioned but one."

"The other was not so foul as that I have described," replied Darcy, in an altered tone, "inasmuch as it was unintentional, and occasioned by no base motive. My wife, your ancestress, was a most lovely woman, and so passionately was I enamoured of her, that I tried by every art to heighten and preserve her beauty. I fed her upon the flesh of capons, nourished with vipers; caused her to steep her lovely limbs in baths distilled from roses and violets; and had recourse to the most potent cosmetics. At last I prepared a draught from poisons—yes, poisons—the effect of which, I imagined, would be wondrous. She drank it, and expired horribly disfigured. Conceive my despair at beholding the fair image of my idolatry destroyed—defaced by my hand. In my frenzy I should have laid violent hands upon myself, if I had not been restrained. Love may again rule my heart—beauty may again dazzle my eyes, but I shall never more feel the passion I entertained for my lost Amice—never more behold charms equal to hers."

And he pressed his hand to his face.

"The mistake you then committed should serve as a warning," said Auriol. "What if it be poison you have now confected? Try a few drops of it on some animal."

"No—no; it is the true elixir," replied Darcy. "Not a drop must be wasted. You will witness its effect anon. Like the snake, I shall cast my slough, and come forth younger than I was at twenty."

"Meantime, I beseech you to render me some assistance," groaned Auriol, "or, while you are preparing for immortality, I shall expire before your eyes."

"Be not afraid," replied Darcy; "you shall take no harm. I will care for you presently; and I understand leechcraft so well, that I will answer for your speedy and perfect recovery."

"Drink, then, to it!" cried Auriol.

"I know not what stays my hand," said the old man, raising the phial; "but now that immortality is in my reach, I dare not grasp it."

"Give me the potion, then," cried Auriol.

"Not for worlds," rejoined Darcy, hugging the phial to his breast. "No; I will be young again—rich—happy. I will go forth into the world—I will bask in the smiles of beauty—I will feast, revel, sing—life shall be one perpetual round of enjoyment. Now for the trial—ha!" and, as he raised the potion towards his lips, a sudden pang shot across his heart. "What is this?" he cried, staggering. "Can death assail me when I am just about to enter upon perpetual life? Help me, good grandson! Place the phial to my lips. Pour its contents down my throat—quick! quick!"

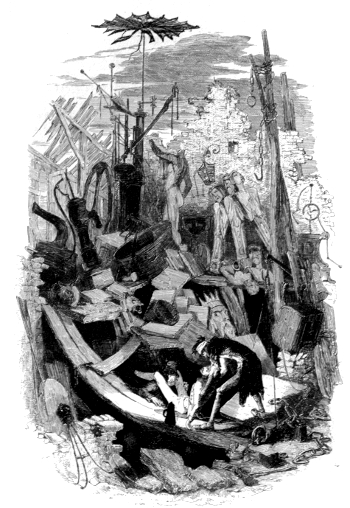

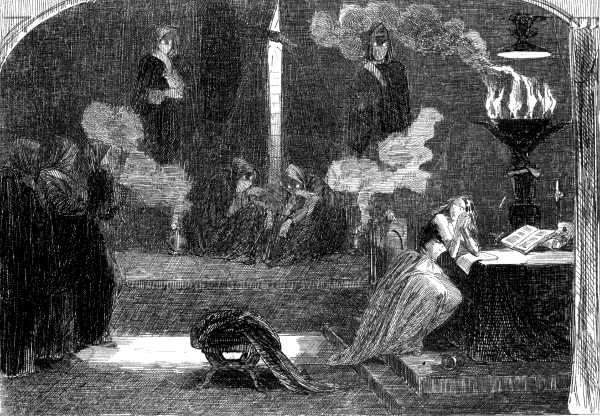

The Elixir of Long Life.

"I am too weak to stir," groaned Auriol. "You have delayed it too long."

"Oh, heavens! we shall both perish," shrieked Darcy, vainly endeavouring to raise his palsied arm,—"perish with the blissful shore in view."

And he sank backwards, and would have fallen to the ground if he had not caught at the terrestrial sphere for support.

"Help me—help me!" he screamed, fixing a glance of unutterable anguish on his relative.

"It is worth the struggle," cried Auriol. And, by a great effort, he raised himself, and staggered towards the old man.

"Saved—saved!" shrieked Darcy. "Pour it down my throat. An instant, and all will be well."

"Think you I have done this for you?" cried Auriol, snatching the potion; "no—no."

And, supporting himself against the furnace, he placed the phial to his lips, and eagerly drained its contents.

The old man seemed paralysed by the action, but kept his eye fixed upon the youth till he had drained the elixir to the last drop. He then uttered a piercing cry, threw up his arms, and fell heavily backwards.

Dead—dead!

Flashes of light passed before Auriol's eyes, and strange noises smote his ears. For a moment he was bewildered as with wine, and laughed and sang discordantly like a madman. Every object reeled and danced around him. The glass vessels and jars clashed their brittle sides together, yet remained uninjured; the furnace breathed forth flames and mephitic vapours; the spiral worm of the alembic became red hot, and seemed filled with molten lead; the pipe of the bolt-head ran blood; the sphere of the earth rolled along the floor, and rebounded from the wall as if impelled by a giant hand; the skeletons grinned and gibbered; so did the death's-head on the table; so did the skulls against the chimney; the monstrous sea-fish belched forth fire and smoke; the bald, decapitated head opened its eyes, and fixed them, with a stony glare, on the young man; while the dead alchemist shook his hand menacingly at him.

Unable to bear these accumulated horrors, Auriol became, for a short space, insensible. On recovering, all was still. The lights within the lamp had expired; but the bright moonlight, streaming through the window, fell upon the rigid features of the unfortunate alchemist, and on the cabalistic characters of the open volume beside him.

Eager to test the effect of the elixir, Auriol put his hand to his side. All traces of the wound were gone; nor did he experience the slightest pain in any other part of his body. On the contrary, he seemed endowed with preternatural strength. His breast dilated with rapture, and he longed to expand his joy in active motion.

Striding over the body of his aged relative, he threw open the window. As he did so, joyous peals burst from surrounding churches, announcing the arrival of the new year.

While listening to this clamour, Auriol gazed at the populous and picturesque city stretched out before him, and bathed in the moonlight.

"A hundred years hence," he thought, "and scarcely one soul of the thousands within those houses will be living, save myself. A hundred years after that, and their children's children will be gone to the grave. But I shall live on—shall live through all changes—all customs—all time. What revelations I shall then have to make, if I should dare to disclose them!"

As he ruminated thus, the skeleton hanging near him was swayed by the wind, and its bony fingers came in contact with his cheek. A dread idea was suggested by the occurrence.

"There is one peril to be avoided," he thought; "ONE PERIL!—what is it? Pshaw! I will think no more of it. It may never arise. I will be gone. This place fevers me."

With this, he left the laboratory, and hastily descending the stairs, at the foot of which he found Flapdragon, passed out of the house.

BOOK THE FIRST

EBBA

CHAPTER I

THE RUINED HOUSE IN THE VAUXHALL ROAD

Late one night, in the spring of 1830, two men issued from a low, obscurely situated public-house, near Millbank, and shaped their course apparently in the direction of Vauxhall Bridge. Avoiding the footpath near the river, they moved stealthily along the farther side of the road, where the open ground offered them an easy means of flight, in case such a course should be found expedient. So far as it could be discerned by the glimpses of the moon, which occasionally shone forth from a rack of heavy clouds, the appearance of these personages was not much in their favour. Haggard features, stamped deeply with the characters of crime and debauchery; fierce, restless eyes; beards of several days' growth; wild, unkempt heads of hair, formed their chief personal characteristics; while sordid and ragged clothes, shoes without soles, and old hats without crowns, constituted the sum of their apparel.

One of them was tall and gaunt, with large hands and feet; but despite his meagreness, he evidently possessed great strength: the other was considerably shorter, but broad-shouldered, bow-legged, long-armed, and altogether a most formidable ruffian. This fellow had high cheek-bones, a long aquiline nose, and a coarse mouth and chin, in which the animal greatly predominated. He had a stubby red beard, with sandy hair, white brows and eyelashes. The countenance of the other was dark and repulsive, and covered with blotches, the result of habitual intemperance. His eyes had a leering and malignant look. A handkerchief spotted with blood, and tied across his brow, contrasted strongly with his matted black hair, and increased his natural appearance of ferocity. The shorter ruffian carried a mallet upon his shoulder, and his companion concealed something beneath the breast of his coat, which afterwards proved to be a dark lantern.

Not a word passed between them; but keeping a vigilant look-out, they trudged on with quick, shambling steps. A few sounds arose from the banks of the river, and there was now and then a plash in the water, or a distant cry, betokening some passing craft; but generally all was profoundly still. The quaint, Dutch-looking structures on the opposite bank, the line of coal-barges and lighters moored to the strand, the great timber-yards and coal-yards, the brewhouses, gasworks, and waterworks, could only be imperfectly discerned; but the moonlight fell clear upon the ancient towers of Lambeth Palace, and on the neighbouring church. The same glimmer also ran like a silver belt across the stream, and revealed the great, stern, fortress-like pile of the Penitentiary—perhaps the most dismal-looking structure in the whole metropolis. The world of habitations beyond this melancholy prison was buried in darkness. The two men, however, thought nothing of these things, and saw nothing of them; but, on arriving within a couple of hundred yards of the bridge, suddenly, as if by previous concert, quitted the road, and, leaping a rail, ran across a field, and plunged into a hollow formed by a dried pit, where they came to a momentary halt.

"You ain't a-been a-gammonin' me in this matter, Tinker?" observed the shorter individual. "The cove's sure to come?"

"Why, you can't expect me to answer for another as I can for myself, Sandman," replied the other; "but if his own word's to be taken for it, he's sartin to be there. I heerd him say, as plainly as I'm a speakin' to you—'I'll be here to-morrow night—at the same hour——'"

"And that wos one o'clock?" said the Sandman.

"Thereabouts," replied the other.

"And who did he say that to?" demanded the Sandman.

"To hisself, I s'pose," answered the Tinker; "for, as I told you afore, I could see no one vith him."

"Do you think he's one of our perfession?" inquired the Sandman.

"Bless you! no—that he ain't," returned the Tinker. "He's a reg'lar slap-up svell."

"That's no reason at all," said the Sandman. "Many a first-rate svell practises in our line. But he can't be in his right mind to come to such a ken as that, and go on as you mentions."

"As to that I can't say," replied the Tinker; "and it don't much matter, as far as ve're consarned."

"Devil a bit," rejoined the Sandman, "except—you're sure it worn't a sperrit, Tinker. I've heerd say that this crib is haanted, and though I don't fear no livin' man, a ghost's a different sort of customer."

"Vell, you'll find our svell raal flesh and blood, you may depend upon it," replied the Tinker. "So come along, and don't let's be frightenin' ourselves vith ould vimen's tales."

With this they emerged from the pit, crossed the lower part of the field, and entered a narrow thoroughfare, skirted by a few detached houses, which brought them into the Vauxhall Bridge Road.

Here they kept on the side of the street most in shadow, and crossed over whenever they came to a lamp. By-and-by, two watchmen were seen advancing from Belvoir Terrace, and, as the guardians of the night drew near, the ruffians crept into an alley to let them pass. As soon as the coast was clear, they ventured forth, and quickening their pace, came to a row of deserted and dilapidated houses. This was their destination.

The range of habitations in question, more than a dozen in number, were, in all probability, what is vulgarly called "in Chancery," and shared the fate of most property similarly circumstanced. They were in a sad ruinous state—unroofed, without windows and floors. The bare walls were alone left standing, and these were in a very tumble-down condition. These neglected dwellings served as receptacles for old iron, blocks of stone and wood, and other ponderous matters. The aspect of the whole place was so dismal and suspicious, that it was generally avoided by passengers after nightfall.

Skulking along the blank and dreary walls, the Tinker, who was now a little in advance, stopped before a door, and pushing it open, entered the dwelling. His companion followed him.

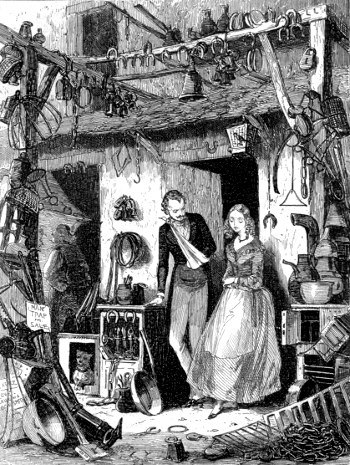

The extraordinary and incongruous assemblage of objects which met the gaze of the Sandman, coupled with the deserted appearance of the place, produced an effect upon his hardy but superstitious nature.

Looking round, he beheld huge mill-stones, enormous water-wheels, boilers of steam-engines, iron vats, cylinders, cranes, iron pumps of the strangest fashion, a gigantic pair of wooden scales, old iron safes, old boilers, old gas-pipes, old water-pipes, cracked old bells, old bird-cages, old plates of iron, old pulleys, ropes, and rusty chains, huddled and heaped together in the most fantastic disorder. In the midst of the chaotic mass frowned the bearded and colossal head of Neptune, which had once decorated the forepart of a man-of-war. Above it, on a sort of framework, lay the prostrate statue of a nymph, together with a bust of Fox, the nose of the latter being partly demolished, and the eyes knocked in. Above these, three garden divinities laid their heads amicably together. On the left stood a tall Grecian warrior, minus the head and right hand. The whole was surmounted by an immense ventilator, stuck on the end of an iron rod, ascending, like a lightning-conductor, from the steam-engine pump.

Seen by the transient light of the moon, the various objects above enumerated produced a strange effect upon the beholder's imagination. There was a mixture of the grotesque and terrible about them. Nor was the building itself devoid of a certain influence upon his mind. The ragged brickwork, overgrown with weeds, took with him the semblance of a human face, and seemed to keep a wary eye on what was going forward below.

A means of crossing from one side of the building to the other, without descending into the vault beneath, was afforded by a couple of planks; though as the wall on the farther side was some feet higher than that near at hand, and the planks were considerably bent, the passage appeared hazardous.

Glancing round for a moment, the Tinker leaped into the cellar, and, unmasking his lantern, showed a sort of hiding-place, between a bulk of timber and a boiler, to which he invited his companion.

The Sandman jumped down.

"The ale I drank at the 'Two Fighting Cocks' has made me feel drowsy, Tinker," he remarked, stretching himself on the bulk; "I'll just take a snooze. Vake me up if I snore—or ven our sperrit appears."

The Tinker replied in the affirmative; and the other had just become lost to consciousness, when he received a nudge in the side, and his companion whispered—"He's here!"

"Vhere—vhere?" demanded the Sandman, in some trepidation.

"Look up, and you'll see him," replied the other.

Slightly altering his position, the Sandman caught sight of a figure standing upon the planks above them. It was that of a young man. His hat was off, and his features, exposed to the full radiance of the moon, looked deathly pale, and though handsome, had a strange sinister expression. He was tall, slight, and well-proportioned; and the general cut of his attire, the tightly-buttoned, single-breasted coat, together with the moustache upon his lip, gave him a military air.

"He seems a-valkin' in his sleep," muttered the Sandman. "He's a-speakin' to some von unwisible."

"Hush—hush!" whispered the other. "Let's hear wot he's a-sayin'."

"Why have you brought me here?" cried the young man, in a voice so hollow that it thrilled his auditors. "What is to be done?"

"It makes my blood run cold to hear him," whispered the Sandman. "Vot d'ye think he sees?"

"Why do you not speak to me?" cried the young man—"why do you beckon me forward? Well, I obey. I will follow you."

And he moved slowly across the plank.

"See, he's a-goin' through that door," cried the Tinker. "Let's foller him."

"I don't half like it," replied the Sandman, his teeth chattering with apprehension. "We shall see summat as'll take avay our senses."

"Tut!" cried the Tinker; "it's only a sleepy-valker. Wot are you afeerd on?"

With this he vaulted upon the planks, and peeping cautiously out of the open door to which they led, saw the object of his scrutiny enter the adjoining house through a broken window.

Making a sign to the Sandman, who was close at his heels, the Tinker crept forward on all fours, and, on reaching the window, raised himself just sufficiently to command the interior of the dwelling. Unfortunately for him, the moon was at this moment obscured, and he could distinguish nothing except the dusky outline of the various objects with which the place was filled, and which were nearly of the same kind as those of the neighbouring habitation. He listened intently, but not the slightest sound reached his ears.

After some time spent in this way, he began to fear the young man must have departed, when all at once a piercing scream resounded through the dwelling. Some heavy matter was dislodged, with a thundering crash, and footsteps were heard approaching the window.

Hastily retreating to their former hiding-place, the Tinker and his companion had scarcely regained it, when the young man again appeared on the plank. His demeanour had undergone a fearful change. He staggered rather than walked, and his countenance was even paler than before. Having crossed the plank, he took his way along the top of the broken wall towards the door.

"Now, then, Sandman!" cried the Tinker; "now's your time!"

The other nodded, and, grasping his mallet with a deadly and determined purpose, sprang noiselessly upon the wall, and overtook his intended victim just before he gained the door.

Hearing a sound behind him, the young man turned, and only just became conscious of the presence of the Sandman, when the mallet descended upon his head, and he fell crushed and senseless to the ground.

The Ruined house in the Vauxhall Road

"The vork's done!" cried the Sandman to his companion, who instantly came up with the dark lantern; "let's take him below, and strip him."

"Agreed," replied the Tinker; "but first let's see wot he has got in his pockets."

"Vith all my 'art," replied the Sandman, searching the clothes of the victim. "A reader!—I hope it's well lined. Ve'll examine it below. The body 'ud tell awkvard tales if any von should chance to peep in."

"Shall we strip him here?" said the Tinker. "Now the darkey shines on 'em, you see what famous togs the cull has on."

"Do you vant to have us scragged, fool?" cried the Sandman, springing into the vault. "Hoist him down here."

With this, he placed the wounded man's legs over his own shoulders, and, aided by his comrade, was in the act of heaving down the body, when the street-door suddenly flew open, and a stout individual, attended by a couple of watchmen, appeared at it.

"There the villains are!" shouted the new-comer. "They have been murderin' a gentleman. Seize 'em—seize 'em!"

And, as he spoke, he discharged a pistol, the ball from which whistled past the ears of the Tinker.

Without waiting for another salute of the same kind, which might possibly be nearer its mark, the ruffian kicked the lantern into the vault, and sprang after the Sandman, who had already disappeared.

Acquainted with the intricacies of the place, the Tinker guided his companion through a hole into an adjoining vault, whence they scaled a wall, got into the next house, and passing through an open window, made good their retreat, while the watchmen were vainly searching for them under every bulk and piece of iron.

"Here, watchmen!" cried the stout individual, who had acted as leader; "never mind the villains just now, but help me to convey this poor young gentleman to my house, where proper assistance can be rendered him. He still breathes; but he has received a terrible blow on the head. I hope his skull ain't broken."

"It is to be hoped it ain't, Mr. Thorneycroft," replied the foremost watchman; "but them was two desperate characters as ever I see, and capable of any hatterosity."

"What a frightful scream I heard to be sure!" cried Mr. Thorneycroft. "I was certain somethin' dreadful was goin' on. It was fortunate I wasn't gone to bed; and still more fortunate you happened to be comin' up at the time. But we mustn't stand chatterin' here. Bring the poor young gentleman along."

Preceded by Mr. Thorneycroft, the watchmen carried the wounded man across the road towards a small house, the door of which was held open by a female servant, with a candle in her hand. The poor woman uttered a cry of horror as the body was brought in.

"Don't be cryin' out in that way, Peggy," cried Mr. Thorneycroft, "but go and get me some brandy. Here, watchmen, lay the poor young gentleman down on the sofa—there, gently, gently. And now, one of you run to Wheeler Street, and fetch Mr. Howell, the surgeon. Less noise, Peggy—less noise, or you'll waken Miss Ebba, and I wouldn't have her disturbed for the world."

With this, he snatched the bottle of brandy from the maid, filled a wine-glass with the spirit, and poured it down the throat of the wounded man. A stifling sound followed, and after struggling violently for respiration for a few seconds, the patient opened his eyes.

CHAPTER II

THE DOG-FANCIER

The Rookery! Who that has passed Saint Giles's, on the way to the city, or coming from it, but has caught a glimpse, through some narrow opening, of its squalid habitations, and wretched and ruffianly occupants! Who but must have been struck with amazement, that such a huge receptacle of vice and crime should be allowed to exist in the very heart of the metropolis, like an ulcerated spot, capable of tainting the whole system! Of late, the progress of improvement has caused its removal; but whether any less cogent motive would have abated the nuisance may be questioned. For years the evil was felt and complained of, but no effort was made to remedy it, or to cleanse these worse than Augean stables. As the place is now partially, if not altogether, swept away, and a wide and airy street passes through the midst of its foul recesses, a slight sketch may be given of its former appearance.

Entering a narrow street, guarded by posts and cross-bars, a few steps from the crowded thoroughfare brought you into a frightful region, the refuge, it was easy to perceive, of half the lawless characters infesting the metropolis. The coarsest ribaldry assailed your ears, and noisome odours afflicted your sense of smell. As you advanced, picking your way through kennels flowing with filth, or over putrescent heaps of rubbish and oyster-shells, all the repulsive and hideous features of the place were displayed before you. There was something savagely picturesque in the aspect of the place, but its features were too loathsome to be regarded with any other feeling than disgust. The houses looked as sordid, and as thickly crusted with the leprosy of vice, as their tenants. Horrible habitations they were, in truth. Many of them were without windows, and where the frames were left, brown paper or tin supplied the place of glass; some even wanted doors, and no effort was made to conceal the squalor within. On the contrary, it seemed to be intruded on observation. Miserable rooms, almost destitute of furniture; floors and walls caked with dirt, or decked with coarse flaring prints; shameless and abandoned-looking women; children without shoes and stockings, and with scarcely a rag to their backs: these were the chief objects that met the view. Of men, few were visible—the majority being out on business, it is to be presumed; but where a solitary straggler was seen, his sinister looks and mean attire were in perfect keeping with the spot. So thickly inhabited were these wretched dwellings, that every chamber, from garret to cellar, swarmed with inmates. As to the cellars, they looked like dismal caverns, which a wild beast would shun. Clothes-lines were hung from house to house, festooned with every kind of garment. Out of the main street branched several alleys and passages, all displaying the same degree of misery, or, if possible, worse, and teeming with occupants. Personal security, however, forbade any attempt to track these labyrinths; but imagination, after the specimen afforded, could easily picture them. It was impossible to move a step without insult or annoyance. Every human being seemed brutalised and degraded; and the women appeared utterly lost to decency, and made the street ring with their cries, their quarrels, and their imprecations. It was a positive relief to escape from this hotbed of crime to the world without, and breathe a purer atmosphere.

Such being the aspect of the Rookery in the daytime, what must it have been when crowded with its denizens at night! Yet at such an hour it will now be necessary to enter its penetralia.

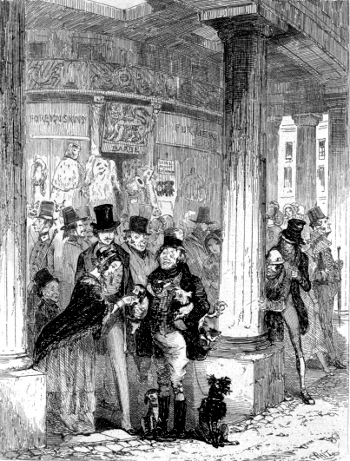

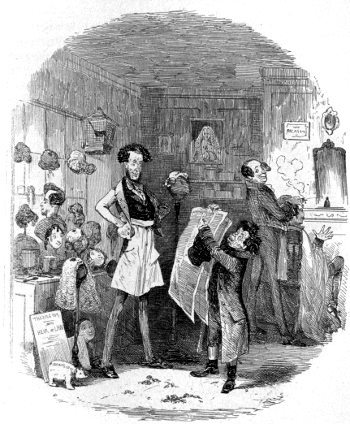

After escaping from the ruined house in the Vauxhall Road, the two ruffians shaped their course towards Saint Giles's, running the greater part of the way, and reaching the Broadway just as the church clock struck two. Darting into a narrow alley, and heedless of any obstructions they encountered in their path, they entered a somewhat wider cross-street, which they pursued for a short distance, and then struck into an entry, at the bottom of which was a swing-door that admitted them into a small court, where they found a dwarfish person wrapped in a tattered watchman's greatcoat, seated on a stool with a horn lantern in his hand and a cutty in his mouth, the glow of which lighted up his hard, withered features. This was the deputy-porter of the lodging-house they were about to enter. Addressing him by the name of Old Parr, the ruffians passed on, and lifting the latch of another door, entered a sort of kitchen, at the farther end of which blazed a cheerful fire, with a large copper kettle boiling upon it. On one side of the room was a deal table, round which several men of sinister aspect and sordid attire were collected, playing, at cards. A smaller table of the same material stood near the fire, and opposite it was a staircase leading to the upper rooms. The place was dingy and dirty in the extreme, the floors could not have been scoured for years, and the walls were begrimed with filth. In one corner, with his head resting on a heap of coals and coke, lay a boy almost as black as a chimney-sweep, fast asleep. He was the waiter. The principal light was afforded by a candle stuck against the wall, with a tin reflector behind it. Before the fire, with his back turned towards it, stood a noticeable individual, clad in a velveteen jacket with ivory buttons, a striped waistcoat, drab knees, a faded black silk neckcloth tied in a great bow, and a pair of ancient Wellingtons ascending half-way up his legs, which looked disproportionately thin when compared with the upper part of his square, robustious, and somewhat pursy frame. His face was broad, jolly, and good-humoured, with a bottle-shaped nose, fleshy lips, and light grey eyes, glistening with cunning and roguery. His hair, which dangled in long flakes over his ears and neck, was of a dunnish red, as were also his whiskers and beard. A superannuated white castor, with a black hat-band round it, was cocked knowingly on one side of his head, and gave him a flashy and sporting look. His particular vocation was made manifest by the number of dogs he had about him. A beautiful black-and-tan spaniel, of Charles the Second's breed, popped its short snubby nose and long silken ears out of each coat-pocket. A pug was thrust into his breast, and he carried an exquisite Blenheim under either arm. At his feet reposed an Isle of Skye terrier, and a partly cropped French poodle, of snowy whiteness, with a red worsted riband round his throat. This person, it need scarcely be said, was a dog-fancier, or, in other words, a dealer in, and a stealer of, dogs, as well as a practiser of all the tricks connected with that nefarious trade. His self-satisfied air made it evident he thought himself a smart, clever fellow,—and adroit and knavish he was, no doubt,—while his droll, plausible, and rather winning manners helped him materially to impose upon his customers. His real name was Taylor, but he was known among his companions by the appellation of Ginger. On the entrance of the Sandman and the Tinker, he nodded familiarly to them, and with a sly look inquired—"Vell, my 'arties—wot luck?"

"Oh, pretty middlin'," replied the Sandman gruffly.

And seating himself at the table, near the fire, he kicked up the lad, who was lying fast asleep on the coals, and bade him fetch a pot of half-and-half. The Tinker took a place beside him, and they waited in silence the arrival of the liquor, which, when it came, was disposed of at a couple of pulls; while Mr. Ginger, seeing they were engaged, sauntered towards the card-table, attended by his four-footed companions.

"And now," said the Sandman, unable to control his curiosity longer, and taking out his pocket-book, "we'll see what fortun' has given us."

The Dog-fancier.

So saying, he unclasped the pocket-book, while the Tinker bent over him in eager curiosity. But their search for money was fruitless. Not a single bank-note was forthcoming. There were several memoranda and slips of paper, a few cards, and an almanac for the year—that was all. It was a great disappointment.

"So we've had all this trouble for nuffin', and nearly got shot into the bargain," cried the Sandman, slapping down the book on the table with an oath. "I vish I'd never undertaken the job."

"Don't let's give it up in sich an 'urry," replied the Tinker; "summat may be made on it yet. Let's look over them papers."

"Look 'em over yourself," rejoined the Sandman, pushing the book towards him. "I've done wi' 'em. Here, lazy-bones, bring two glasses o' rum-and-water—stiff, d'ye hear?"

While the sleepy youth bestirred himself to obey these injunctions, the Tinker read over every memorandum in the pocket-book, and then proceeded carefully to examine the different scraps of paper with which it was filled. Not content with one perusal, he looked them all over again, and then began to rub his hands with great glee.

"Wot's the matter?" cried the Sandman, who had lighted a cutty, and was quietly smoking it. "Wot's the row, eh?"

"Vy, this is it," replied the Tinker, unable to contain his satisfaction; "there's secrets contained in this here pocket-book as'll be worth a hundred pound and better to us. We ha'n't had our trouble for nuffin'."

"Glad to hear it!" said the Sandman, looking hard at him. "Wot kind o' secrets are they?"

"Vy, hangin' secrets," replied the Tinker, with mysterious emphasis. "He seems to be a terrible chap, and to have committed murder wholesale."

"Wholesale!" echoed the Sandman, removing the pipe from his lips. "That sounds awful. But what a precious donkey he must be to register his crimes i' that way."

"He didn't expect the pocket-book to fall into our hands," said the Tinker.

"Werry likely not," replied the Sandman; "but somebody else might see it. I repeat, he must be a fool. S'pose we wos to make a entry of everythin' we does. Wot a nice balance there'd be agin us ven our accounts comed to be wound up!"

"Ourn is a different bus'ness altogether," replied the Tinker. "This seems a werry mysterious sort o' person. Wot age should you take him to be?"

"Vy, five-an'-twenty at the outside," replied the Sandman.

"Five-an'-sixty 'ud be nearer the mark," replied the Tinker. "There's dates as far back as that."

"Five-an'-sixty devils!" cried the Sandman; "there must be some mistake i' the reckonin' there."

"No, it's all clear an' reg'lar," rejoined the other; "and that doesn't seem to be the end of it neither. I looked over the papers twice, and one, dated 1780, refers to some other dokiments."

"They must relate to his granddad, then," said the Sandman; "it's impossible they can refer to him."

"But I tell 'ee they do refer to him," said the Tinker, somewhat angrily, at having his assertion denied; "at least, if his own word's to be taken. Anyhow, these papers is waluable to us. If no one else believes in 'em, it's clear he believes in 'em hisself, and will be glad to buy 'em from us."

"That's a view o' the case worthy of an Old Bailey lawyer," replied the Sandman. "Wot's the gemman's name?"

"The name on the card is Auriol Darcy," replied the Tinker.

"Any address?" asked the Sandman.

The Tinker shook his head.

"That's unlucky agin," said the Sandman. "Ain't there no sort o' clue?"

"None votiver, as I can perceive," said the Tinker.

"Vy, zounds, then, ve're jist vere ve started from," cried the Sandman. "But it don't matter. There's not much chance o' makin' a bargin vith him. The crack o' the skull I gave him has done his bus'ness."

"Nuffin' o' the kind," replied the Tinker. "He alvays recovers from every kind of accident."

"Alvays recovers!" exclaimed the Sandman, in amazement. "Wot a constitootion he must have!"

"Surprisin'!" replied the Tinker; "he never suffers from injuries—at least, not much; never grows old; and never expects to die; for he mentions wot he intends doin' a hundred years hence."

"Oh, he's a lu-nattic!" exclaimed the Sandman, "a downright lu-nattic; and that accounts for his wisitin' that 'ere ruined house, and a-fancyin' he heerd some one talk to him. He's mad, depend upon it. That is, if I ain't cured him."

"I'm of a different opinion," said the Tinker.

"And so am I," said Mr. Ginger, who had approached unobserved, and overheard the greater part of their discourse.

"Vy, vot can you know about it, Ginger?" said the Sandman, looking up, evidently rather annoyed.

"I only know this," replied Ginger, "that you've got a good case, and if you'll let me into it, I'll engage to make summat of it."

"Vell, I'm agreeable," said the Sandman.

"And so am I," added the Tinker.

"Not that I pays much regard to wot you've bin a readin' in his papers," purused Ginger; "the gemman's evidently half-cracked, if he ain't cracked altogether—but he's jist the person to work upon. He fancies hisself immortal—eh?"

"Exactly so," replied the Tinker.

"And he also fancies he's committed a lot o' murders?" perused Ginger.

"A desperate lot," replied the Tinker.

"Then he'll be glad to buy those papers at any price," said Ginger. "Ve'll deal vith him in regard to the pocket-book, as I deals vith regard to a dog—ask a price for its restitootion."

"We must find him out first," said the Sandman.

"There's no difficulty in that," rejoined Ginger. "You must be constantly on the look-out. You're sure to meet him some time or other."

"That's true," replied the Sandman; "and there's no fear of his knowin' us, for the werry moment he looked round I knocked him on the head."

"Arter all," said the Tinker, "there's no branch o' the perfession so safe as yours, Ginger. The law is favourable to you, and the beaks is afeerd to touch you. I think I shall turn dog-fancier myself."

"It's a good business," replied Ginger, "but it requires a hedication. As I wos sayin', we gets a high price sometimes for restorin' a favourite, especially ven ve've a soft-hearted lady to deal vith. There's some vimen as fond o' dogs as o' their own childer, and ven ve gets one o' their precious pets, ve makes 'em ransom it as the brigands you see at the Adelphi or the Surrey sarves their prisoners, threatenin' to send first an ear, and then a paw, or a tail, and so on. I'll tell you wot happened t'other day. There wos a lady—a Miss Vite—as was desperate fond of her dog. It wos a ugly warmint, but no matter for that—the creater had gained her heart. Vell, she lost it; and, somehow or other, I found it. She vos in great trouble, and a friend o' mine calls to say she can have the dog agin, but she must pay eight pound for it. She thinks this dear, and a friend o' her own adwises her to wait, sayin' better terms will be offered; so I sends vord by my friend that if she don't come down at once the poor animal's throat vill be cut that werry night."

"Ha!—ha!—ha!" laughed the others.

"Vell, she sent four pound, and I put up with it," pursued Ginger; "but about a month arterwards she loses her favourite agin, and, strange to say, I finds it. The same game is played over agin, and she comes down with another four pound. But she takes care this time that I shan't repeat the trick; for no sooner does she obtain persession of her favourite than she embarks in the steamer for France, in the hope of keeping her dog safe there."

"Oh! Miss Bailey, unfortinate Miss Bailey!—Fol-de-riddle-tol-ol-lol—unfortinate Miss Bailey!" sang the Tinker.

"But there's dog-fanciers in France, ain't there?" asked the Sandman.

"Lor' bless 'ee, yes," replied Ginger; "there's as many fanciers i' France as here. Vy, ve drives a smartish trade wi' them through them foreign steamers. There's scarcely a steamer as leaves the port o' London but takes out a cargo o' dogs. Ve sells 'em to the stewards, stokers, and sailors—cheap—and no questins asked. They goes to Ostend, Antverp, Rotterdam, Hamburg, and sometimes to Havre. There's a Mounseer Coqquilu as comes over to buy dogs, and ve takes 'em to him at a house near Billinsgit market."

"Then you're alvays sure o' a ready market somehow," observed the Sandman.

"Sartin," replied Ginger, "cos the law's so kind to us. Vy, bless you, a perliceman can't detain us, even if he knows ve've a stolen dog in our persession, and ve svears it's our own; and yet he'd stop you in a minnit if he seed you with a suspicious-lookin' bundle under your arm. Now, jist to show you the difference atwixt the two perfessions:—I steals a dog—walue, maybe, fifty pound, or p'raps more. Even if I'm catched i' the fact I may get fined twenty pound, or have six months' imprisonment; vile, if you steals an old fogle, walue three fardens, you'll get seven years abroad, to a dead certainty."

"That seems hard on us," observed the Sandman reflectively.

"It's the law!" exclaimed Ginger triumphantly. "Now, ve generally escapes by payin' the fine, 'cos our pals goes and steals more dogs to raise the money. Ve alvays stands by each other. There's a reg'lar horganisation among us; so ve can alvays bring vitnesses to svear vot ve likes, and ve so puzzles the beaks, that the case gets dismissed, and the constable says, 'Vich party shall I give the dog to, your vorship?' Upon vich, the beak replies, a-shakin' of his vise noddle, 'Give it to the person in whose persession it was found. I have nuffin' more to do vith it.' In course the dog is delivered up to us."

"The law seems made for dog-fanciers," remarked the Tinker.

"Wot d'ye think o' this?" pursued Ginger. "I wos a-standin' at the corner o' Gray's Inn Lane vith some o' my pals near a coach-stand, ven a lady passes by vith this here dog—an' a beauty it is, a real long-eared Charley—a follerin' of her. Vell, the moment I spies it, I unties my apron, whips up the dog, and covers it up in a trice. Vell, the lady sees me, an' gives me in charge to a perliceman. But that si'nifies nuffin'. I brings six vitnesses to svear the dog vos mine, and I actually had it since it vos a blind little puppy; and, wot's more, I brings its mother, and that settles the pint. So in course I'm discharged; the dog is given up to me; and the lady goes avay lamentin'. I then plays the amiable, an' offers to sell it her for twenty guineas, seein' as how she had taken a fancy to it; but she von't bite. So if I don't sell it next week, I shall send it to Mounseer Coqquilu. The only vay you can go wrong is to steal a dog wi' a collar on, for if you do, you may get seven years' transportation for a bit o' leather and a brass plate vorth a shillin', vile the animal, though vorth a hundred pound, can't hurt you. There's law again—ha, ha!"

"Dog-fancier's law!" laughed the Sandman.

"Some of the Fancy is given to cruelty," pursued Ginger, "and crops a dog's ears, or pulls out his teeth to disguise him; but I'm too fond o' the animal for that. I may frighten old ladies sometimes, as I told you afore, but I never seriously hurts their pets. Nor did I ever kill a dog for his skin, as some on 'em does."

"And you're always sure o' gettin' a dog, if you vants it, I s'pose?" inquired the Tinker.

"Alvays," replied Ginger. "No man's dog is safe. I don't care how he's kept, ve're sure to have him at last. Ve feels our vay with the sarvents, and finds out from them the walley the master or missis sets on the dog, and soon after that the animal's gone. Vith a bit o' liver, prepared in my partic'lar vay, I can tame the fiercest dog as ever barked, take him off his chain, an' bring him arter me at a gallop."

"And do respectable parties ever buy dogs knowin' they're stolen?" inquired the Tinker.

"Ay, to be sure," replied Ginger; "sometimes first-rate nobs. They put us up to it themselves; they'll say, 'I've jist left my Lord So-and-So's, and there I seed a couple o' the finest pointers I ever clapped eyes on. I vant you to get me jist sich another couple.' Vell, ve understands in a minnit, an' in doo time the identicle dogs finds their vay to our customer."

"Oh! that's how it's done?" remarked the Sandman.

"Yes, that's the vay," replied Ginger. "Sometimes a party'll vant a couple o' dogs for the shootin' season; and then ve asks, 'Vich vay are you a-goin'—into Surrey or Kent?' And accordin' as the answer is given ve arranges our plans."

"Vell, yourn appears a profitable and safe employment, I must say," remarked the Sandman.

"Perfectly so," replied Ginger. "Nothin' can touch us till dogs is declared by statute to be property, and stealin' 'em a misdemeanour. And that won't occur in my time."

"Let's hope not," rejoined the other two.

"To come back to the pint from vich we started," said the Tinker; "our gemman's case is not so surprisin' as it at first appears. There are some persons as believe they never will die—and I myself am of the same opinion. There's our old deputy here—him as ve calls Old Parr—vy, he declares he lived in Queen Bess's time, recollects King Charles bein' beheaded perfectly vell, and remembers the Great Fire o' London, as if it only occurred yesterday."

"Walker!" exclaimed Ginger, putting his finger to his nose.

"You may larf, but it's true," replied the Tinker. "I recollect an old man tellin' me that he knew the deputy sixty years ago, and he looked jist the same then as now,—neither older nor younger."

"Humph!" exclaimed Ginger. "He don't look so old now."

"That's the cur'ousest part of it," said the Tinker. "He don't like to talk of his age unless you can get him i' the humour; but he once told me he didn't know why he lived so long, unless it were owin' to a potion he'd swallowed, vich his master, who was a great conjurer in Queen Bess's days, had brew'd."

"Pshaw!" exclaimed Ginger. "I thought you too knowin' a cove, Tinker, to be gulled by such an old vife's story as that."

"Let's have the old fellow in and talk to him," replied the Tinker. "Here, lazy-bones," he added, rousing the sleeping youth, "go an' tell Old Parr ve vants his company over a glass o' rum-an'-vater."

CHAPTER III

THE HAND AND THE CLOAK

A furious barking from Mr. Ginger's dogs, shortly after the departure of the drowsy youth, announced the approach of a grotesque-looking little personage, whose shoulders barely reached to a level with the top of the table. This was Old Parr. The dwarfs head was much too large for his body, as is mostly the case with undersized persons, and was covered with a forest of rusty black hair, protected by a strangely shaped seal-skin cap. His hands and feet were equally disproportioned to his frame, and his arms were so long that he could touch his ankles while standing upright. His spine was crookened, and his head appeared buried in his breast. The general character of his face seemed to appertain to the middle period of life; but a closer inspection enabled the beholder to detect in it marks of extreme old age. The nose was broad and flat, like that of an ourang-outang; the resemblance to which animal was heightened by a very long upper lip, projecting jaws, almost total absence of chin, and a retreating forehead. The little old man's complexion was dull and swarthy, but his eyes were keen and sparkling.

His attire was as singular as his person. Having recently served as double to a famous demon-dwarf at the Surrey Theatre, he had become possessed of a cast-off pair of tawny tights, an elastic shirt of the same material and complexion, to the arms of which little green bat-like wings were attached, while a blood-red tunic with vandyke points was girded round his waist. In this strange apparel his diminutive limbs were encased, while additional warmth was afforded by the greatcoat already mentioned, the tails of which swept the floor after him like a train.

Having silenced his dogs with some difficulty, Mr. Ginger burst into a roar of laughter, excited by the little old man's grotesque appearance, in which he was joined by the Tinker; but the Sandman never relaxed a muscle of his sullen countenance.

Their hilarity, however, was suddenly checked by an inquiry from the dwarf, in a shrill, odd tone, "Whether they had sent for him only to laugh at him?"

"Sartainly not, deputy," replied the Tinker. "Here, lazy-bones, glasses o' rum-an'-vater, all round."

The drowsy youth bestirred himself to execute the command. The spirit was brought; water was procured from the boiling copper; and the Tinker handed his guest a smoking rummer, accompanied with a polite request to make himself comfortable.

Opposite the table at which the party were seated, it has been said, was a staircase—old and crazy, and but imperfectly protected by a broken hand-rail. Midway up it stood a door equally dilapidated, but secured by a chain and lock, of which Old Parr, as deputy-chamberlain, kept the key. Beyond this point the staircase branched off on the right, and a row of stout wooden banisters, ranged like the feet of so many cattle, was visible from beneath. Ultimately, the staircase reached a small gallery, if such a name can be applied to a narrow passage communicating with the bedrooms, the doors of which, as a matter of needful precaution, were locked outside; and as the windows were grated, no one could leave his chamber without the knowledge of the landlord or his representative. No lights were allowed in the bedrooms, nor in the passage adjoining them.

Conciliated by the Tinker's offering, Old Parr mounted the staircase, and planting himself near the door, took off his greatcoat, and sat down upon it. His impish garb being thus more fully displayed, he looked so unearthly and extraordinary that the dogs began to howl fearfully, and Ginger had enough to do to quiet them.

Silence being at length restored, the Tinker, winking slyly at his companions, opened the conversation.

"I say, deputy," he observed, "ve've bin havin' a bit o' a dispute vich you can settle for us."

"Well, let's see," squeaked the dwarf. "What is it?"

"Vy, it's relative to your age," rejoined the Tinker. "Ven wos you born?"

"It's so long ago, I can't recollect," returned Old Parr rather sulkily.

"You must ha' seen some changes in your time?" resumed the Tinker, waiting till the little old man had made some progress with his grog.

"I rayther think I have—a few," replied Old Parr, whose tongue the generous liquid had loosened. "I've seen this great city of London pulled down, and built up again—if that's anything. I've seen it grow, and grow, till it has reached its present size. You'll scarcely believe me, when I tell you, that I recollect this Rookery of ours—this foul vagabond neighbourhood—an open country field, with hedges round it, and trees. And a lovely spot it was. Broad Saint Giles's, at the time I speak of, was a little country village, consisting of a few straggling houses standing by the roadside, and there wasn't a single habitation between it and Convent Garden (for so the present market was once called); while that garden, which was fenced round with pales, like a park, extended from Saint Martin's Lane to Drury House, a great mansion situated on the easterly side of Drury Lane, amid a grove of beautiful timber."

"My eyes!" cried Ginger, with a prolonged whistle; "the place must be preciously transmogrified indeed!"

"If I were to describe the changes that have taken place in London since I've known it, I might go on talking for a month," pursued Old Parr. "The whole aspect of the place is altered. The Thames itself is unlike the Thames of old. Its waters were once as clear and bright above London Bridge as they are now at Kew or Richmond; and its banks, from Whitefriars to Scotland Yard, were edged with gardens. And then the thousand gay wherries and gilded barges that covered its bosom—all are gone—all are gone!"

"Those must ha' been nice times for the jolly young vatermen vich at Black friars wos used for to ply," chanted the Tinker; "but the steamers has put their noses out o' joint."

"True," replied Old Parr; "and I, for one, am sorry for it. Remembering, as I do, what the river used to be when enlightened by gay craft and merry company, I can't help wishing its waters less muddy, and those ugly coal-barges, lighters, and steamers away. London is a mighty city, wonderful to behold and examine, inexhaustible in its wealth and power; but in point of beauty it is not to be compared with the city of Queen Bess's days. You should have seen the Strand then—a line of noblemen's houses—and as to Lombard Street and Gracechurch Street, with their wealthy goldsmiths' shops—but I don't like to think of 'em."

"Vell, I'm content vith Lunnun as it is," replied the Tinker, "'specially as there ain't much chance o' the ould city bein' rewived."

"Not much," replied the dwarf, finishing his glass, which was replenished at a sign from the Tinker.

"I s'pose, my wenerable, you've seen the king as bequeathed his name to these pretty creaters," said Ginger, raising his coat-pockets, so as to exhibit the heads of the two little black-and-tan spaniels.

"What! old Rowley?" cried the dwarf—"often. I was page to his favourite mistress, the Duchess of Cleveland, and I have seen him a hundred times with a pack of dogs of that description at his heels."

"Old Rowley wos a king arter my own 'art," said Ginger, rising and lighting a pipe at the fire. "He loved the femi-nine specious as well as the ca-nine specious. Can you tell us anythin' more about him?"